This blog post is the first in a (short) series that will summarize the findings of a literature scan and consultation on the topic of youth engagement. The posts are inspired by some work that InsideOut Policy Research is doing with a national foundation that funds (among other things) violence-prevention and capacity-building programming for youth. This foundation is leading an initiative designed to enhance – at a systems level – the capacity of non-profit sector organizations to deliver effective programming that supports young people to have healthy relationships and live violence-free lives. The initiative brings together service providers, funders, policy makers and researchers to identify opportunities for collective efforts that might address some of the key challenges facing the field of teen anti-violence work. However, a challenge currently confronting the project steering committee is how to engage young people – the intended beneficiaries of the initiative – as meaningful partners in the process itself.

Meaningful youth engagement is no easy task

The McCreary Centre Society (Vancouver, BC) defines youth engagement in formal decision making as: “The meaningful participation and sustainable involvement of young people in shared decisions in matters which affect their lives and those of their community, including planning, decision making and program delivery” (McCreary Centre Society, 2009).

Stakeholders involved in the initiative to build the field of teen anti-violence work are sensitive both to the importance of involving youth in the process as well as to the difficulties inherent in making such involvement meaningful and authentic. When adults gather in the guise of “experts” to determine how best to help youth, the effort is fundamentally missing the point if the voice of youth is absent. But simply having youth present is not sufficient for meaningful youth engagement. Too often, the nature of the youth involvement is defined (and confined) by processes created by adults, youth are tasked with peripheral or relatively unimportant activities, and consequently, their engagement and participation wanes.

Organizations and committees (dominated by adults) need to develop – in concert with youth – processes that support young people’s contribution to organizational decision making. According to the Students Commission (the lead for the Centre of Excellence for Youth Engagement) these processes need to:

- Be predicated on respect for young people’s opinions and competencies;

- Facilitate a balance of power between adults and youth;

- Promote young people’s sense of belonging and importance to the organization; and

- Enable youth to contribute on their own terms.

A model for understanding the dynamics of youth engagement

In its published literature, the Students Commission has articulated a coherent theoretical model of youth engagement. One of the considerable strengths of the model is that it has been co-created by youth and adults, and tested and refined over a number of years.

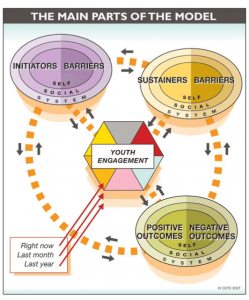

The model incorporates four key components: 1) the youth engagement activity itself; 2) the factors that are likely to encourage a young person to become involved in an organization (“initiating factors”); 3) the factors that are likely to keep her or him involved (“sustaining factors”); and, 4) the impacts or outcomes of the involvement. The model is represented visually thus (McCart & Khanna, n.d.):

In this model, the youth engagement activity comprises a number of important aspects: the breadth, intensity and duration of involvement; the quality of the experience; the location or setting of the activity; the co-participants; the goals of the activity; and the specific features of the activity.

The factors that initiate youth engagement and the factors that sustain youth engagement are understood to operate on three levels: self (individual or personal), social and system. For example, a young person may decide to become involved with an organization because:

- Its mission aligns with their interests or values (self);

- A good friend or trusted teacher has recommended the organization (social); and/or

- The political context has given rise to an opportunity to address an issue through active participation (system).

A young person’s continued involvement in an organization may be supported by:

- Their innate commitment to sticking with something (self);

- The new friendships they have made at the organization (social); and/or

- Opportunities to become involved in the organization’s decision-making process (system).

The model also frames outcomes of youth engagement as occurring at the levels of self, social and system. Examples of the first include personal skills development, improvements in physical health, and enhanced mental and emotional wellbeing. Outcomes at the social level may include new relationships and an increase in social support. System-level outcomes include, for instance, partnerships with adult organizations, integration of youth into the wider community, and increased civil engagement.

Finally, all four components of the model are understood to be in a dynamic and mutually reinforcing relationship with each other as well as being subject to change over time. In other words, the reasons why a young person becomes and stays involved in an organization, and how they perceive the impacts of that involvement, will inform their experience of the engagement. Similarly, the young person’s experience with an organization will shape the factors that sustain their involvement and the reasons why they may choose to become involved with another group or agency. A young person’s degree of engagement with an organization may differ in degree over time – it may wax and wane, for example, according to the benefits the youth is deriving from it, the competing demands on their time, their evolving interests and experience and their changing developmental status.

From concept to practice

The Students Commission model of youth engagement is intended to be used and adapted by organizations to support their understanding of the dynamics of youth engagement and the relationships between key components of the process. Design and implementation of a youth engagement process also requires an understanding of the principles and features that support positive participation by youth. These will be the focus of my next blog post on youth engagement.